Insights

Can income assets help protect your portfolio from inflation?

Craig Alexander and Liam Donnelly

Published 12 July 2022

ANALYSIS: Inflation acts like a tax, reducing the original purchasing power of the investor’s money.

Inflation-linked bonds are another option for income investors.

Today, we’re going to discuss what investors searching for income – typically in cash and fixed interest investments – might wish to think about when protecting their income returns from the risk of rising inflation.

While there are many types of fixed interest investments, for now we’ll stick with the concept of a debt security, in this case a bond.

The simplest bonds with the least moving parts are sometimes referred to as nominal bonds, as they pay a single contracted fixed rate of return (or coupon) until maturity.

In theory, the nominal bond yield is calculated to reflect a number of factors that encourage and compensate a buyer for purchasing and holding a bond.

In summary, think about economic and political certainty or uncertainty, the issuer’s ability to make good on its obligations around payment of interest and principal, as well as a number of other variables – such as inflation.

But what happens if the investors’ expectations of the future rate of inflation turn out to be wrong?

Inflation-linked bond an option

Inflation acts like a tax, reducing the original purchasing power of the investor’s money when later received as coupons and repaid principal.

Instead, another bond investment for income investors could be an inflation-linked bond, where the potential return to the investor is better linked to the rate of inflation.

Indeed, inflation-linked bonds (also known as inflation-indexed bonds) have a much longer history than most would expect – the first known inflation-linked bond dates back to 1780 when the Commonwealth of Massachusetts issued these debt securities to soldiers in the Revolutionary War: deferred compensation for service that would retain purchasing power.

So how does an inflation-linked bond work? First, let’s quickly look at the differences between a nominal and inflation-linked bond.

In simple terms, an inflation-linked bond differs from a nominal bond in that its theoretical value is primarily linked to changes in the rate of inflation; in New Zealand this is the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Domestically, as the CPI increases, the principal of the bond increases, boosting the value of coupons and the principal to be paid back.

Remember, nominal bonds usually pay a fixed coupon to the investor which means reducing purchasing power if inflation turns out to be higher than anticipated.

In a nutshell, inflation-linked bonds better protect the purchasing power of bond income, as compared to nominal bonds, when inflation is rising by giving investors a return that takes into account the impact of inflation, by delivering a return that is a real yield rather than a nominal yield.

As a professional investor we’ve struggled to understand why inflation-linked bonds aren’t more popular in this current period of rising inflation.

Undoubtedly there may be some risk aversion at play, as no investment is riskless, and should the inflation rate fall, then the inflation-linked bond coupon payments and the principal paid back, could reduce – and potentially by more than expected, meaning in hindsight a nominal bond could have been the better option.

Local supply restricted

However, we think it’s probably more to do with the fact that local supply has been restricted; the largest arranger by far and away in Aotearoa is NZ Debt Management (NZDM), selling inflation-linked bonds on behalf of the New Zealand Government to a select number of professional investors.

Additionally, there simply hasn’t been the same level of participation from non-Government issuers, such as corporates and local councils, as there has been in the local nominal bond market.

Furthermore, our assessment of the issuance track record of Government inflation-linked bonds is that the NZDM has been pragmatic, balancing the need for the Government to raise money against investor demand.

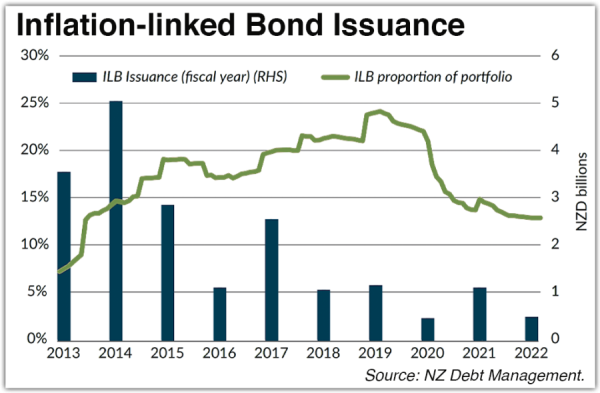

Inflation linked-bond issuance began in 1977, peaking at around 24% of all Government debt in 2019 and more recently falling to around 13% as at the end of April 2022.

However, we were delighted to see in this year’s Budget an accompanying bulletin entitled, “Supporting the New Zealand Inflation Indexed Bond Market”, released by the NZDM.

In the bulletin the NZDM laid out its case to better support the local inflation-linked bond market; initially promoting liquidity through offering to buy back the shorter-dated 2025 bonds and at the same time ensuring an appropriate supply of 10 year benchmark inflation-linked bonds.

The regulator’s most recent data as at the end of May 2022 lists households as holding $ 621 million of nominal government bonds and only $39 million of inflation-indexed bonds, which ironically – given the recent increasing rate of domestic inflation – is lower than the $ 52 million held at the end of May 2020.

Disclaimer: This article has been prepared in good faith based on information obtained from sources believed to be reliable and accurate. It does not contain financial advice. Octagon Asset Management Limited is the investment manager for the Octagon Investment Funds and Summer KiwiSaver scheme, which have investment exposures to both New Zealand Government nominal and inflation-index bonds. This article was supplied free to NBR and first published 12 July 2022.