Brain drains and inflation pain

Tobias Newton

Published 25 October 2022

ANALYSIS: Key swing factor for NZ's net migration outcome is relative strength between New Zealand and Australian labour markets.

New Zealand net migration has been a hot topic of late. As our economy has continued to expand beyond 2019 levels (even as borders have remained closed) New Zealand’s unemployment rate has dropped to the lowest levels ever recorded. This has increased turnover in our labour force as New Zealand businesses bid up the price of labour in their efforts to fulfil robust demand for their goods and services, nevertheless the large number of vacancies persist.

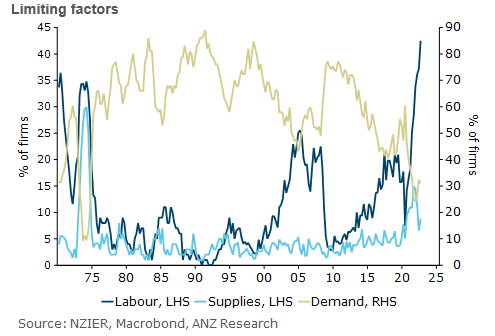

Recently the NZ Institute of Economic Research (NZIER) published its survey of business opinion for the September quarter. This confirmed how tight conditions are, with firms responding cautiously to questions about capacity constraints, trading conditions and confidence levels going forward. The dark blue line on the chart below (from ANZ research) represents the share of firms citing access to labour as a limiting factor to their output levels. This percentage is currently at levels last seen in the 1970’s, with labour shortages affecting almost half of New Zealand firms surveyed.

In order to offset labour market pressure New Zealand businesses have lobbied for an easing of immigration settings. These efforts appear to have gained some traction recently as visa numbers and requirements are being relaxed. The latest moves by the government include lifting the cap on seasonal migrant workers by 3,000 (+19%), removing New Zealand qualification requirements for migrant chefs and announcing the reopening of skilled migrant and parents visa categories. Current labour shortages are acute, particularly in our key export sectors, and upside inflation risks and weakening poll numbers suggest further relaxation to these settings is likely.

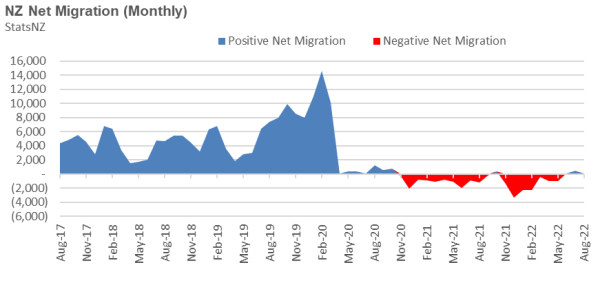

Some commentators have likened the current episode of negative net migration to ‘Brain Drains’ of the past including during the Australian mining boom of 2011/12. This period saw negative annual net migration persist for some two and a half years, with a peak annual loss of ~17,500 people. From March 2020 up until earlier this year (as Omicron surged and New Zealand’s border restrictions remained in place), net migration outflows peaked with a loss of ~16,500 in the twelve months to February 2022.

However, a closer look at the monthly data show that for the last six months the annual outflow/deficit has in fact been shrinking. We have had flat to modestly positive monthly net migration through June, July and August of this year despite speculation that a wave of young people are taking deferred OE’s to Europe and/or chasing higher real incomes in Australia.

Source: StatsNZ

The key swing factor for New Zealand’s net migration outcome is the relative strength between the New Zealand and Australian labour markets. Close proximity and unrestricted work rights mean labour flows freely between our two countries. When unemployment falls in Australia relative to New Zealand’s unemployment we typically see more Kiwis leaving for Australia than returning and the inverse is also true when unemployment rises there. We’ve observed some interesting developments in the Australian labour market in recent months.

For example, the Internet Vacancies Index (IVI) produced by the Australian government measures the number of online job advertisements each month. From the beginning of this year, as the Australian labour market gathered momentum, online job advertisements also grew strongly, peaking at some 305,000 in June of this year. In the midst of rapidly rising interest rates, falling household wealth and living cost pressures we have seen a drop off in job advertisements over the last quarter, with the number of active job advertisements for September down (-7.2%) on June of this year. In addition, the KPMG global CEO outlook survey (firms with a minimum of USD $500m in revenue) published mid-October showed 78% of Australian respondents had taken steps to prepare for an expected downturn, either by planning or implementing a recruitment freeze.

It is not yet clear how rampant inflation, rising interest rates and recession fears in the UK and Europe will influence behaviour of young people planning their OEs. Continued conflict in Ukraine and the related energy crises in Europe suggest our economy may fare relatively better (at least over the near term). Whether this changes travel intentions is yet to be seen, however it would make sense to see fewer people leave should employment opportunities offshore become more difficult to obtain.

Provisional migration estimates and leading indicators suggest the current episode of the ‘brain drain’ has already passed its peak. If this is the case, it stands to reason that our labour market may have also reached a point of inflection and is past peak tightness for this cycle. Any softening here will affect workforce wage demands with a lag. The risk of a ‘wage price’ spiral as a source of surging domestic inflation has been of particular concern to the RBNZ (and other global central banks) in recent monetary policy reviews. Right now, there is a consensus that interest rates will continue to rise through the first part of next year, staying at elevated levels through all of 2023 and well into 2024. A softening labour market would provide scope for earlier rate cuts, perhaps this rates’ cycle could turn sooner than the market expects.

Disclaimer: This article has been prepared in good faith based on information obtained from sources believed to be reliable and accurate. It does not contain financial advice. This article was supplied free to NBR and first published 25 October 2022.