Bonds. Global bonds. Stirred, not shaken

Craig Alexander and Liam Donnelly

ANALYSIS: The question is - international fixed interest, and if not, why not?

Bonds are often seen as less glamorous, less volatile, and basically boring when compared with the high-octane, high-risk, and highly volatile equities market. Think more George Smiley and less ‘double-0-seven’. But this has been far from the case this year, when the bond market has stirred with some vengeance and shaken just about everyone and everything, including the equity market. In New Zealand, we have an array of bonds available to investors issued by various government and non-government entities. We are confident that an investor can reasonably say we have a varied and fairly sophisticated bond market. One way to get an idea of what’s available to fixed-interest investors is to take a look at the NZX’s debt market or the New Zealand Debt Management’s (NZDM) website. The diversity of issuers, tenor, and risk is clear. So, given the variety of issuance that is available in New Zealand, why do investors need to look offshore for fixed interest (bond) investments? We think there are several reasons why an investor would want to diversify their portfolio with global or international bonds. A quick glance at Morningstar’s September 2023 KiwiSaver Report indicates that about 20% of KiwiSaver assets are held in ‘International bonds’, so many professional fund managers in New Zealand think there is a place for them in a disciplined, well-diversified portfolio. Are they right, or is this a case of groupthink?

Let’s start with the numbers

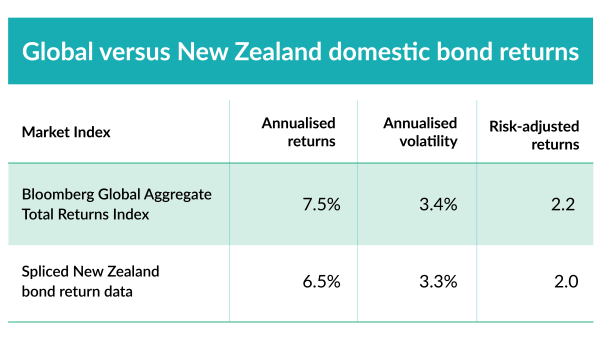

When assessing different investments, professional investors often think about risk-adjusted returns; is an investment fairly rewarding the investor for the amount of risk taken? Our preference when calculating a risk-adjusted return is the annualised return divided by annualised standard deviation (a measure of the volatility of returns). In the table below, we compare two series of return data. First, the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Total Return Index (100% hedged to the New Zealand dollar) for offshore bonds. Then we need to create a blended index for the domestic data. Due to the paucity of an equivalent return series, we’ve calculated a spliced measure of returns from the past performance of New Zealand Government bonds, New Zealand non-Government bonds and, more recently, the Bloomberg NZ Bond Composite 0+ Year index. We’ve assessed that, when blended, these indices serve as a good proxy for the returns of a broad-based portfolio of New Zealand bonds. While there will always be some debate as to how far back we should source data, we’ve settled for just over 30 years, starting from approximately 1990. What we’ve tried to capture in both domestic and global jurisdictions are the risk-adjusted returns of a diversified, investable portfolio. In the table below, the higher the number, the better the message; historically, international bonds have delivered greater risk-adjusted returns than a broadly equivalent investment in New Zealand bonds.

Source: ANZ NZ Government index data goes from 1990 to 1994. S&P/NZX A- Grade Corporate Bond Index data covers the period of 1994 to 2001 before the inception of the Investment Grade Bond Index data filling in the time periods from 2001 to 2011. And, Bloomberg NZ Bond Composite 0+ Yr Index fills in the present data since 2011.

History always repeats, or does it?

Notwithstanding how far back we go when collecting investment return data, there is no guarantee that history will indeed repeat this time around, or that this time is, in fact, going to be any different. To improve our rigour, we overlay some contemporary assumptions in order to make the historic return data better calibrated to current reality and, that way, more forward looking. We readily admit that this is more of an art than a science, however we’ve found Government 10-year bond rates to be a reasonable predictor of possible bond returns over the medium term. Currently, the New Zealand Government 10-year bond rate is close to 5.0% while the equivalent US Government bond rate is broadly 4.40%. Our analysis of the historic risk-adjusted returns strongly suggests local investors should head overseas for a greater risk-adjusted return, while our observation of Government 10-year bonds suggests fixed-interest investors should stay at home. So, which is right?

More to investing than just returns

What about the other risks that investors’ face? It’s not just the return and volatility risks. When an investor makes the decision to invest in bonds, just like any other investment, they know they are subjecting themselves to a number of risks, such as credit risk, default risk, execution risk, and liquidity risk, among others. Investing in foreign currency bonds introduces a further idiosyncratic risk – currency risk. Our thinking is to mitigate foreign currency risk as we’re after the foreign bond investment exposure and not motivated to speculate on the direction of foreign currency markets. Even so, any form of foreign currency hedging is technically difficult with an additional series of execution and pricing risks.

Go global or stay at home?

We need to start our assessment somewhere and assessing risk-adjusted returns is the logical place to begin when trying to determine whether to gain exposure to offshore bonds. Oftentimes, we’ve found that empirical evidence serves us well to shape initial conversations and to displace deeply held opinions masqueraded as the facts. In the chart, we’ve added another market index to display the returns associated with a well-diversified portfolio of non-Government Australian bonds. For comparability purposes, we’ve rebased the historic returns starting from 2013 as we’re after a high-level view. We note that these returns roughly approximate each other and are broadly synchronised.

Source: Refinitiv, Bloomberg

However, investors also need to think about the potential for events to occur that are not captured in the historical record of returns. New Zealand is a small, isolated country with an increasing number of natural disaster and weather-related risks. Called tail-risks or black swan events, these sort of events typically have a substantial negative impact on investments, but are incredibly hard to predict and value under a traditional risk-adjusted return framework. Also, what of the concentration risk of holding both the equity and bonds in the same New Zealand companies? Surely it would be best to avoid a double whammy should things go wrong. This is a good place to start a discussion but is hard to quantify from basic historic data. And finally, what about the scale of the market? By definition, an international market is generally larger than a domestic market and with that come all the opportunities – some good and some not so good – of being able to transact with a significantly larger number of buyers and sellers in deeper, more liquid markets. Ahead of any liquidity or credit crunch, how do you assess the likely activities of market participants that may have a different risk appetite to a similar group of domestic investors? Very difficult indeed.

Good enough for the regulator, then good enough for all

Interestingly, our own Reserve Bank of New Zealand has just posted a speech titled, ‘Building a balance sheet to support financial stability’. The speech, delivered in November stated the RBNZ’s intent to increase its holdings of foreign currency debt securities. The goal being that a more diversified portfolio of assets will be more effective when the regulator is next required to provide financial assistance to distressed domestic markets.

The rational investor

Investment diversification – the art and the science of thinking beyond the initial quantitative analysis – probably explains why many professional fund managers in New Zealand, including ourselves, have investment exposures to both New Zealand and international fixed interest. When diversification is coupled with some harder-to-quantify but nevertheless important positives that potentially reduce risk, then the question in our mind and for any rational investor is international fixed interest; if not, why not? Is this truly rational investment behaviour or just deeply held opinions masqueraded as facts? We think it is rational and factual, a question more suited to George Smiley answering rather than James Bond.

Craig Alexander and Liam Donnelly.

Craig Alexander is head of fixed interest at Octagon Asset Management. He has more than 25 years of experience spanning New Zealand’s banking, insurance, and fund management industries. Liam Donnelly joined Octagon in 2022 as fixed interest analyst having previously worked in research at Forsyth Barr.

Disclaimer: This article has been prepared in good faith based on information obtained from sources believed to be reliable and accurate. This article does not contain financial advice. Octagon Asset Management is the investment manager for Octagon Investment Funds and Summer KiwiSaver scheme and some of the portfolios own securities issued by companies mentioned in this article.